[ad_1]

With four banks down in the US and Europe and at least several more wobbling, we’re currently in the throes of the worst banking strife since 2007-08. Aggressive interest rate hikes have meant that banks are sitting on hefty losses on their portfolios of government bonds – some $2 trillion (£1.6 trillion) or 15% losses on US banks alone.

This makes many banks vulnerable to the same kind of funding problems that brought down Silicon Valley Bank – one in ten banks are sitting on even greater losses and tighter funding, putting the lie to any idea that SVB was unusual. There may well be potential for further bank runs as anxious customers withdraw their money: US banks alone have over $1 trillion in uninsured customer deposits. All eyes will be on Deutsche Bank and First Republic to see if they can overcome the market jitters of the past few days.

The Federal Reserve and other central banks are reassuring everyone that the financial system is sound and bears little comparison to 2008. Nonetheless, there are a number of foreseeable consequences for the medium term that are barely being discussed yet.

1. Weaker bank lending

When someone borrows money, they normally have to pay extra to borrow for a longer duration than a shorter duration, because it’s generally riskier to lend further into the future. But this flips when investors get nervous about the immediate future, which is what has happened right now (we say the yield curve has inverted). This points to a recession in the coming months.

Banks are already reluctant to lend because they are having to pay more to borrow from one another at today’s interest rates. Therefore the broader economic uncertainty is likely to make it even harder for consumers and businesses to get credit. In the aftermath of the 2007-09 crisis, US bank lending fell by almost 11% .

2. Government borrowing difficulties

Banks have got into trouble from investing in long-term government bonds, supposedly one of the safest assets in the market, which raises questions about to what extent they will be willing to do so in future. Governments typically issue bonds of upwards of a year to finance longer term or larger-scale investments, but may find this harder at a time when there are hefty bills to pay.

For instance the ageing of the huge baby boomer generation is putting significant pressure on healthcare, requiring heavy government investment into medical research, healthcare infrastructure and extra workers. The green industrial policy agenda entails enormous costs too.

If banks are not willing to buy long-term bonds are readily as before, the cost of borrowing will rise at a time when most governments are already struggling with high levels of debt.

3. More inflation

Central banks could step in and buy more government bonds directly to provide their governments with the necessary funds. Unfortunately this is tricky, since such purchases would potentially increase the money supply and make inflation worse than it is already.

Inflation has tailed down a little in countries such as the US and UK since the peaks of 2022, but is still well above the 2% target. If central banks have to directly support more government borrowing, expect more upward pressure on prices. This in turn will put more pressure on central banks to keep interest rates higher.

So far, the Federal Reserve (the US central bank), has tried to minimise the damage by setting up a facility to allow banks to borrow against their government bonds at book value. In just a couple of weeks, US banks have already borrowed nearly half a trillion US dollars. But again, there are limits to how much assistance can be provided without jeopardising the fight against inflation.

4. Fewer jobs

So far, the jobs market in the US and also the UK has been fairly resilient. But if credit becomes more scarce and there is a recession, that situation could change quite quickly.

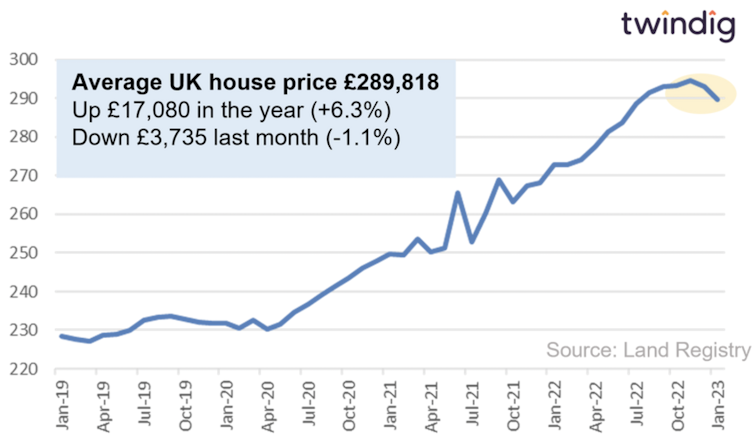

5. Lower house prices

The housing market in the US and UK has also held up quite well, despite higher interest rates. But in an environment of prolonged high interest rates and reduced bank lending, house prices could start falling more sharply: after the 2007-09 crisis, US house prices fell by almost 20%.

UK average house prices

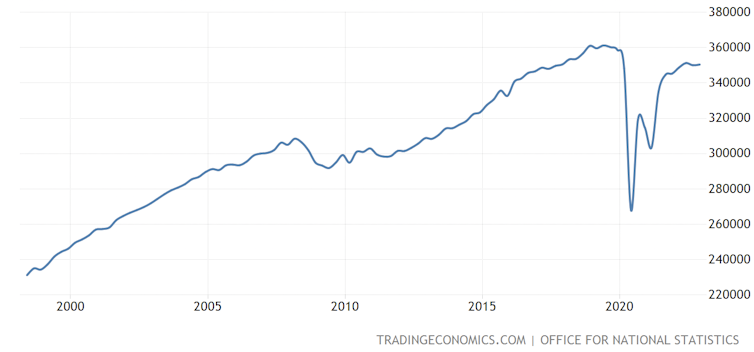

6. Less consumer spending

With households already having to find more to cover higher mortgage payments, consumer spending is struggling. A fall in house prices and a rise in unemployment will further affect how wealthy people think they are, which could further reduce how much they are willing to spend.

UK consumer spending

Trading Economics

7. The demise of smaller banks

To prevent bank runs, governments could also step in and potentially insure all customer deposits: in the US, for example, customers’ money is only safe up to $250 000, while in the UK it’s £85 000. The problem with extending this protection is that it would be both expensive and difficult to get past politicians since it means rescuing wealthy people.

This is why US treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, recently said this wasn’t an option, except maybe for big banks whose collapse could pose a systemic risk – meaning it could threaten the entire global banking system. Yet if you give greater deposit protection to these banks, you make them safer than the smaller banks – indeed, they already have tougher funding requirements in the US.

The danger is that more and more customers move their money to the bigger banks, making it more likely that the smaller banks collapse. Consumers would then have fewer banks to choose from and could end up paying higher prices for financial services or have less access to financial products.

This all points to tough choices ahead for governments and central banks. At the very least it looks likely that interest rates will need to come down to help protect banks, which may mean that we have to live with higher inflation for longer than most people were expecting.![]()

Konstantinos Lagos is senior lecturer in Business and Economics, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[ad_2]

Source link

(This article is generated through the syndicated feed sources, Financetin doesn’t own any part of this article)