[ad_1]

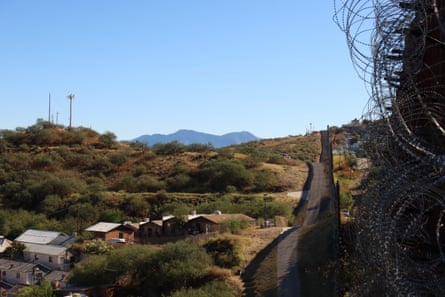

A new map detailing the location of hundreds of surveillance towers is providing the most comprehensive public look yet at the growing virtual wall at the United States’ southern border.

The map, published this month by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a non-profit focused on digital privacy, free speech and innovation, tallies more than 300 existing and 50 proposed surveillance towers along the US-Mexico border.

The largest expansion of surveillance towers that Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is considering, according to the map, would take place near the El Paso port of entry. CBP also plans to deploy a surveillance tower at the peak of Mount Kuchamaa, a sacred mountain for the Kumeyaay people in southern California, the EFF found.

The EFF map does not include every tower built or planned, but was researched by the foundation through document requests, interviews with ranchers, visits to the border, and a review of satellite imagery and Google street view captures, according to Dave Maass, the EFF’s director of investigations.

Maass said he spent long hours searching through satellite images for the distinctive clover leaf shape of autonomous surveillance towers developed by the tech defence company Anduril – the newest type of tower being installed at the southern border. “The satellite image of Anduril is burned into my head,” he said.

The Anduril towers operate day and night and use AI to detect “objects of interest” such as humans or vehicles. The cameras pan 360 degrees and can detect people from 1.7 miles (2.8km) away. When they identify an object, the towers send a notification to border agents. CBP has described the towers as “a partner that never sleeps, never needs to take a coffee break, never even blinks”.

The towers are part of a web of systems meant to monitor and deter migration and smuggling across the US-Mexico border that includes drones, licence plate readers, checkpoints, ground sensors, and data and biometrics collection.

Both Republican and Democratic administrations have invested in such systems since the early 2000s. CBP is prioritising the deployment of border tech “to enhance awareness and strengthen safety in US border regions”, a spokesperson for the agency said, adding that the towers help detect and track irregular migration and suspicious vehicles.

Critics say, however, that the “prevention through deterrence” strategy pursued by several administrations has driven migration through deserts and mountains, leading thousands of migrants to die or go missing. The remains of nearly 10,000 migrants have been found by the border patrol in the last 25 years. A University of Arizona study found that surveillance towers in Arizona were significantly correlated with increased deaths of migrants because they took longer routes through the desert to avoid detection.

Meanwhile, the push for so-called “smart security” is helping to fuel a global security market that is now worth $45bn, according to a recent report by the Imarc Group, a market research company. Anduril spent $930,000 in 2021 and $940,000 in 2022 lobbying the US Senate, the House of Representatives and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) on budget decisions including for autonomous surveillance tower funding, according to lobbying disclosures viewed by the Guardian.

More towers, more deaths

Different types of surveillance towers have popped up along the border in the last two decade, and altogether CBP said it has more than 600 surveillance towers operating near the northern and southern borders.

But the agency says it has so far deployed 195 autonomous surveillance towers and plans to add 80 more. CBP is also deploying upgraded remote video surveillance systems (RVSS), a type of tower built by General Dynamics that can detect a person up to 7.5 miles (12km) away. CBP said it has deployed 256 upgraded RVSS towers already, and plans to add another 75 in fiscal year 2023.

According to the DHS fiscal year 2023 budget for CBP, the agency wants to consolidate all surveillance towers into a single program and ultimately sustain 723 towers along the northern and southern US borders.

The area where CBP is focusing most of its surveillance tower expansion, the EFF found, is the border near the El Paso port of entry, located at the point where Texas, New Mexico and the Mexican state of Chihuahua meet. CBP has approved sites for the deployment of two dozen new surveillance towers there, according to the EFF. Asked when it plans to deploy the towers, CBP declined to comment.

Juárez, on the Mexican side of the border, and El Paso have seen large numbers of migrants arrive in recent months. In reaction to people arriving at the southern border, the Biden administration unveiled a plan to deny claims by asylum seekers who pass through another country and arrive in the US without authorization. The UN High Commissioner on Refugees has urged Biden to reconsider, saying this will force people to return to dangerous situations, which is prohibited under international law.

The area is also a hotspot for border tensions and can be dangerous for migrants. This week, 40 people died in a fire in a Juárez migrant detention centre. Human rights advocates have blamed their deaths on overcrowding and poor immigration policy. This past winter, large numbers of migrants crossing into El Paso exceeded shelter capacity as temperatures dropped, leaving them freezing in the street. “We had hundreds, if not thousands, of migrants living in downtown El Paso on the streets,” said Fernando García, executive director of the Border Network for Human Rights.

García said surveillance intrudes on the privacy and asylum rights of migrating families and children, and questioned how the collected data will be used. According to CBP, the DHS and CBP “continuously review” their policies and practices to respect dignity; safeguard privacy, civil rights and civil liberties; protect against discrimination; and increase transparency and accountability.

García believes that the combination of restrictive immigration policies and proposed surveillance towers near El Paso will not stop migration but push asylum seekers to take more brutal paths, including crossing near Antelope Wells at the western New Mexico border and through the mountainous region along the Texas border south-east of El Paso.

García pointed to two people who died crossing the border “in the middle of nowhere” to evade detection. Jakelin Caal Maquin, a seven-year-old girl from Guatemala, died near Antelope Wells after days of walking through the desert. In another case, Armando Alejo Hernández ran out of water and disappeared while traversing rough terrain near Eagle Peak in Texas, south-east of El Paso.

after newsletter promotion

Rather than funding border surveillance, García argues, funding should instead be directed to welcome centres and more resources for processing asylum claims.

“This is incredibly bipartisan how they have created the conditions for more people to die at the border,” García said. “We want [the Biden administration] to stop and re-evaluate the deterrence operations.”

CBP said smugglers are to blame for migrant deaths because they “continue to recklessly endanger the lives of individuals they smuggle”. The agency said it prevents migrant deaths by communicating the dangers of irregular migration and investing in rescue capabilities. “Preventing loss of life is core to CBP’s mission and our personnel endeavour to rescue those in distress,” the agency said.

A 2021 report by the Arizona-based humanitarian group No More Deaths challenged the characterization of CBP as a rescue agency. The group analysed thousands of calls to a crisis line for missing migrants and found that if a migrant becomes lost in the borderlands there is only a one-in-three chance that the border patrol will search for them.

Sacred mountain

The EFF also found a bunch of planned towers in southern California, where CBP has seen an increase in irregular border crossings. Among them is a planned surveillance tower at the peak of Mount Kuchamaa, a mountain next to the border in southern California that rises 3,885ft above sea level, providing a clear view of the borderlands.

The mountain is sacred to the Kumeyaay Indigenous people on both sides of the border, who hold vision quests and purification ceremonies on the summit. “For these people, the peak is a special place, marking the location for acquisition of knowledge and power by shamans,” according to the National Register of Historic Places.

A communications tower and a small building already stand at the peak. CBP acknowledged it has a project on the mountain but said it does not include construction of a new surveillance tower. The agency said it was replacing existing communications equipment on the tower and the circuits inside the building, and reinforcing the tower’s structure. The agency didn’t say what equipment it was adding to the tower. Maass said documents the EFF obtained say the project will be both a communications and surveillance tower, and the CBP statement wasn’t clear about whether the agency will be attaching surveillance equipment to the existing tower.

Kumeyaay communities have long fought against border wall construction and surveillance. Gwendolyn Parada, chairwoman of the La Posta Band of Mission Indians, said existing infrastructure on the mountain and border patrol vehicles driving up and down directly interfere with religious practices, and new equipment will only add to that intrusion. “I wish they would never have started going on that mountain, because that mountain’s very sacred,” she said.

CBP said it consulted 13 Indigenous nations about the project and two said there would be no adverse impacts. The agency didn’t say how the other nations responded. Parada said CBP had not asked for her community’s consent to build anything. “I wish they would contact us and have a consultation,” she said.

Unintended consequences

Asked if it could provide data showing the effectiveness of border surveillance towers over time, CBP said that it has a process to evaluate impacts of its border deployments, but did not provide numbers.

Maass is doubtful that more surveillance will deter migration: “I am sceptical that this is going to have any impact on stemming immigration – this stuff has never proven itself to be particularly effective,” he said. “But you know, there are always unintended consequences and we’re not really sure what those consequences will be.”

[ad_2]

Source link